Defense industry organizations develop and deploy secure information solutions to protect military and civilian lives.

By Courtney E. Howard

“The only truly secure system is one that is powered off, cast in a block of concrete, and sealed in a lead-lined room with armed guards—and even then I have my doubts,” says Eugene H. Spafford, a professor of computer science at Purdue University, a member of the President’s Information Technology Advisory Committee (PITAC), and a computer security expert and advisor to government agencies and corporations.

Spafford’s statement paints a bleak picture, but it drives home the very real and critical challenges faced by today’s security professionals responsible for protecting classified information, and thereby national security—and ultimately military and civilian lives.

“According to the National Security Administration, over a hundred countries are working on techniques to penetrate our information infrastructure,” said Senator Jon Kyl (R-Arizona). “Many of them are aimed at the Defense Department and high security areas in the private sector and the government, so it’s a very serious threat.”

Information security in military environments is a high priority. A wealth of resources, both financial and intellectual, are being applied by governments and industry organizations to gather, provide secure access to, covertly transmit, and protect data.

Intelligence spending

“The aggregate amount appropriated to the NIP [National Intelligence Program] for fiscal year 2007 was $43.5 billion,” Mike McConnell, director of National Intelligence in Washington, disclosed to the public at the end of October. Funds are appropriated by Congress for the NIP, formerly the National Foreign Intelligence Program. “Any and all subsidiary information concerning the intelligence budget, whether the information concerns particular intelligence agencies or particular intelligence programs, will not be disclosed. Beyond the disclosure of the top-line figure, there will be no other disclosures of currently classified budget information because such disclosures could harm national security.”

This annual figure, which has not been revealed in nearly a decade, since 1998, includes appropriations for the Central Intelligence Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research, FBI intelligence programs, and other Defense Department intelligence collection agencies, such as the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and the National Reconnaissance Office.

The figure does not include the intelligence budgets devoted to Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities (TIARA), or intelligence-related activities such as programs supporting the operating units of the armed services, and the Joint Military Intelligence Program (JMIP), of primary concern to the Department of Defense. The addition of intelligence programs of separate military services is thought to bring the nation’s total annual intelligence spending to more than $50 billion.

The intelligence community is involved not only in collecting information, but also in identifying, understanding, and counteracting intelligence threats from foreign powers. The National Operations Security (OPSEC) Program is designed to identify, control, and protect unclassified information and evidence associated with U.S. national security programs and activities.

Additional defensive measures include communications security, computer security, and such proactive endeavors as clandestine operations and the promulgation of misinformation. Counterintelligence, as defined in Executive Order 12333, includes information gathered and activities conducted “to protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage, or assassination conducted on behalf of foreign powers, organizations, or persons, or international terrorist activities, but not including personnel, physical documents, or communications security.”

Canada’s conundrum

At the same time McConnell was revealing U.S. investment in intelligence, the Auditor General of Canada, Sheila Fraser, was unveiling revelations about the vulnerabilities of that country’s national information.

In the “October 2007 Report of the Auditor General” to Parliament in Ottawa, Fraser describes Canada’s weaknesses in protecting top-secret government information and assets, which poses security threats to Canada, NATO, and the United States.

As concerns government contracts issued to the public sector, Fraser found “serious weaknesses in the processes that are supposed to ensure the safeguarding of sensitive government information and assets entrusted to industry. It is not known to what extent government information and assets have been exposed to risk and who is accountable for that risk.”

In her report, however, Fraser finds fault with the Canadian Department of National Defence, Defence Construction Canada, and Public Works and Government Services Canada for security deficiencies in issuing and verifying the security clearances given to domestic and foreign contractors. “We found serious problems in the system that is supposed to ensure the security of government information and assets entrusted to industry,” Fraser explains. “I am particularly concerned about failures to identify security requirements for major defense construction projects.”

Has Canada unknowingly been giving away U.S. secrets and those of its other military allies? “I don’t believe so, but it’s impossible to know,” admits Fraser. “Clearly we are not protecting our sensitive information.”

In short, the report indicated that: “the Department cannot always ensure that the appropriate procedures have been followed to safeguard sensitive government information in the hands of contractors,” “sensitive contracts have been awarded before contractors have met all the security requirements,” and “contracts were awarded on average about 11 months before the clearances were completed.” PWGSC was unable to demonstrate that the contractors did not access sensitive information or assets during the life of the contract. The Industrial Security Program has the ability to track such contracts and those awarded with clearances pending; however, it does not systematically follow up to ensure that risk mitigation measures are in place.

Defence Construction Canada (DCC), a Crown corporation, is the contracting authority for government defense projects; as such, DCC is responsible for ensuring that individuals and corporations have been screened for security, that sensitive information and assets are safeguarded. DCC has awarded more than 8,500 contracts since April 2002 on behalf of National Defence; yet, National Defence did not provide a Security Requirements Checklist for roughly 99 percent of these contracts. “As a result, neither the Department nor DCC had any assurance that contractors who received these contracts had been cleared to the appropriate security levels,” reads the report. “To varying degrees, these contractors had free access to construction sites and project information that in many cases were sensitive.”

This failure in industrial security provided unscreened contractors and workers access to the plans and construction site of the North American Aerospace Defense (NORAD) Above Ground Complex in North Bay, Ontario—a building designed to have a vital role in North American security and to house very sensitive and highly classified material. Given that Canadian and foreign contractors without security clearance had access to the building plans and the construction site, National Defence does not know whether information or the building itself has been compromised.

Netcentric needs

Data security is integral to the U.S. Department of Defense’s vision of a network-centric battlefield, in which military personnel are connected as nodes on a network and can gain access to the information they need when they need it.

Secure access, which involves denying access to unauthorized entities, is the first line of defense against misuse of critical data. To that end, the U.S. federal government is investing $345 million in identity and access management (IAM).

Researchers at Input in Reston, Va., expect the federal IAM market to grow by 6.2 percent annually through 2012. “Vendor Opportunities Emerge out of HSPD-12 Delays,” Input’s new report, analyzes potential prospects for industry vendors as agencies work to comply with Federal Information Security mandates. “Vendor opportunities will emerge,” says Chris Campbell, a senior analyst with Input, “as agencies begin to actively upgrade physical security systems and IT assets.”

“Particularly in military applications, the large amounts of data gathered and stored need to have very tight access controls to ensure information integrity,” says Mike Ascher, business unit director of military and aerospace services and solutions at Ciprico Inc. in Plymouth, Minn., which provides high-performance, rugged storage systems for data acquisition and analysis applications in military environments.

“In many cases, the best way to secure data is to physically limit access to the data,” Ascher continues. ”More and more technologies and systems are being developed by the storage and networking industries to strictly control the access and transmission of critical information that is being collected on a daily basis. Electronic data access controls and encryption continue to improve to provide solutions that ensure information does not end up in the hands of those that can exploit it.”

Combat communiqué

The exchange of sensitive, classified, and sometimes top-secret data is essential in netcentric tactical environments. Military networks must be secure, and data exchange protected from potential security breaches. In an effort to protect confidential communications on the battlefield, Secure Computing Corp. in San Jose, Calif., and General Dynamics Canada in Ottawa, designed the MESHnet Firewall for use in combat vehicles.

“The confidentiality of communications between armored vehicles is crucial to soldiers’ safety and the success of their mission,” says Rick Bracken, project manager, General Dynamics Canada. “The MESHnet Firewall consolidates all major Internet functions into one.”

MESHnet incorporates Secure Computing’s Sidewinder Evaluation Assurance Level 4 (EAL4) common-criteria-certified firewall ruggedized to Military Standard 810 and enclosed in a conduction-cooled chassis, enabling its use on mounted and dismounted military platforms in harsh military environments. The firewall ensures only authorized data is exchanged, and detects and prevents intrusion attempts and viruses in data flow. The solution delivers application-layer, opposed to network-level, protection given that 70 percent of all attacks occur at the application layer today, according to a representative of General Dynamics.

Secure information transmission in military environments also is a focus Nauman Arshad, technical product marketing manager for Network Centric Infrastructure Products at Curtiss-Wright Controls Embedded Computing in Leesburg, Va.

Some of Curtiss-Wright’s latest processing boards, single-board computers, and digital signal processors, sport quad integrated communications controllers (QUICC) from Freescale in Austin, Texas. ”Freescale’s 8555E PowerPC QUICC System on Chip has a security engine built into the hardware for encryption, decryption, and authentication,” explains Arshad. “The 8555E makes for a good security management processor for Curtiss-Wright’s routers. The 6U VME-682 FireBlade, 6U VPX-684 FireBlade II, and SMS-682 SwitchBox routers use Curtiss-Wright’s PMC-110 CryptoNet, which includes the 8555E processor and integrated software security stacks. The 682, 684, SMS-682, 110 are COTS products that can be used to create networks within air, land, and sea defense platforms. Using products like these, defense systems integrators can build secure networked systems.”

The company’s routers leverage the hardware-enabled cryptographic capability of the Freescale 8555E. That is, standards-based algorithms protect data at rest (stored information) or data in motion (transmitted information). Curtiss-Wright has also integrated a firewall, access control lists, network address translation, IPSec (Internet protocol security), and IP on the 8555E to enable secure data communications.

“Our routers focus on using standards-based cryptography and key protocols like Internet Protocol versions 4 and 6 (IPv4/v6), which can enable secure communications,” says Arshad. “IPv6 has two extension headers that help enable secure communications: 1. Authentication Header (AH) which is used to ensure the authenticity of the IP packet. It is meant to defend against packet spoofing and any illegal changes to the fixed fields. 2. Encrypted Security Payload (ESP) which is used to encapsulate and encrypt the data. It is meant to ensure that only the destination node reads the data.”

“Security is becoming ubiquitous,” Arshad notes. “The need for security is finding its way into COTS-based products. More resources are being networked in the theatre of operations and the amount of data to be secured is increasing; this requires hardware-enabled security because software-based security is too slow to encrypt/decrypt all that traffic.

“Network-centric warfare, the Global Information Grid, and the move to adopt IPv6 are driving the use of networks and IPv6 in defense systems,” Arshad continues. “These initiatives create a networking infrastructure that requires security. As a result, the DOD is pushing many security initiatives.”

COTS and custom cryptography

Representatives at Xilinx Inc. in San Jose, Calif., announced the results of its joint technology development project with The National Security Agency (NSA) in line with the Department of Defense’s Crypto Modernization initiatives. The project culminated in the industry’s first FPGA-based single-chip cryptographic solution, enabled by Xilinx Virtex-4 FPGAs and demonstrated at the Software Radio Summit Technical Conference last February.

The jointly developed solution is based on NSA requirements for high-grade cryptographic processing. Its development required an analysis of the security and ability of Virtex-4 FPGAs to allow independent functions on a single chip.

“This new technology allows the information assurance industry to maximize the advantages of programmable logic to obtain a true COTS solution to what has historically been a custom process,” explains Eric Sivertson, general manager for Aerospace and Defense at Xilinx.

Conversely, the Unified Cryptographic Processor (unityCP) from the L-3 Communications Communication Systems-East (L-3 CS-East) division in Camden, N.J., is a custom component certified by the National Security Agency. L-3’s unityCP is a programmable, Type 1 cryptographic, application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) that is embedded in End Crypto Units to enable secure air, ground, and space communications. NSA certification validates the use of unityCP for the protection of Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information (TS/SCI) and below data traffic, while also managing cryptographic keys at multiple security levels, says a source at L-3 CS-East.

“The unityCP custom ASIC will enable fixed and programmable cryptography and key management supporting multiple simultaneous algorithms at high data rates, meeting the U.S. government’s Crypto Modernization Initiative requirements,” says Gregory B. Roberts, president and chief operating officer of L-3 CS-East. “The unityCP is radiation-hardened for space applications and is suitable for embedment applications in harsh environments.”

Problems with portability

Even despite iron-clad data access and data networking technologies, data can still walk off. Statistics vary, but roughly one in ten laptop computers is stolen, as are one in four PDAs and cell phones, and these figures don’t take into account those that are lost or misplaced. Even security-centric organizations such as the Transportation Security Administration, the U.S. state department, the U.S. Department of Justice, the British military, and the FBI have fallen victim to laptop thieves and lost sensitive national security, law enforcement, and defense information.

Smaller storage devices and drives pose an even greater security risk than mobile computers. Inexpensive, high-capacity, and readily available portable storage devices are now capable of saving multiple catalogs, manuals, and spreadsheets of classified information on a single, easily concealed drive.

Reports in recent months suggested that the British military had banned the use of Apple iPods and other MP3 players. “With USB devices, if you plug it straight into the computer you can bypass passwords and get right on the system,” admits Royal Air Force Wing Commander Peter D’Ardenne. “That’s why we had to plug that gap.”

“We have a flexible management approach in regards to iPods and similar devices that can move data from official systems,” insists a Ministry of Defence spokesperson. “In each area, the risks are assessed and, when appropriate, measures are taken to mitigate that risk.” Representatives reveal that such portable storage devices are not allowed in specific areas, but deny an outright ban on iPods and similar gadgets.

Flash USB drives, commonly called thumb drives, present a significant security challenge. Their small size and ease of use enable users to smuggle confidential data quickly and effortlessly, with little chance of detection. For these and other reasons, the Executive Office of the President of the United States recommended in a memorandum that government agencies encrypt all mobile devices and computers.

The IronKey from IronKey Inc. in Los Altos, Calif., is a hardware-encrypted flash drive designed to protect data from unauthorized users. It is encased in a rugged, potted metal housing and filled with an epoxy-based potting compound that seals all the components and prevents the IronKey from being crushed, even under extremely high pressure. The IronKey also exceeds military waterproof standards (MIL-STD-810F) and employs tamper-reaction technology in the Crypochip, protecting key storage areas with thin-film metal shielding. The chip itself defends against power attacks, invasive actions, and scanning of the onboard memory with an electron microscope; it will self-destruct if an attack is detected. IronKey’s patent-pending “flash-trash” technology carries out a hardware erase of all flash and Cryptochip memory.

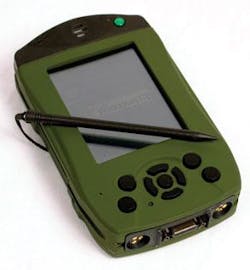

On a slightly larger scale, L-3 Communication Systems-East is developing a next-generation portable, encrypted communications unit in conjunction with the NSA. The L-3 Guardian secure mobile environment portable electronic device (SME PED) delivers secure wireless voice and data communications and the combined functionality of a wireless phone and a personal digital assistant (PDA).

The L-3 Guardian enables secure wireless access to classified (SIPRNET) and unclassified (NIPRNET) networks, as well as the Internet, and features Type 1 and Non-Type 1 encryption algorithms to protect classified data at rest. The handheld unit uses the Secure Communications Interoperable Protocol and is compatible with the High Assurance Internet Protocol Encryptor Interoperability Specification for secure interoperability with classified packet data networks.

Mobile encryption

Increasingly, warfighters are carrying mobile data devices—laptops, PDAs, smartphones, and more—containing vital information that, if captured by enemy combatants, could cause tremendous harm to our troops in the field, acknowledges a representative from SMobile Systems in Columbus, Ohio.

U.S. Army officials, recognizing the need to secure these mobile data devices, have begun fielding handheld devices with SMobile Systems’s mobile security technology to Army mortar battalions in Iraq and Afghanistan.

SMobile Systems’ products securely protect mobile phones from hackers, viruses, data compromise, unauthorized data theft, and the effects of lost or stolen devices. The company’s security solutions offer virus and malware detection, text message and data filtering, prevention of unwanted messages, spam blocking, enterprise management, protection from harmful data on open networks, and data security and password-protection for content and files.

Officials at the DOD, the General Services Administration, and the Office of Management and Budget selected Mobile Armor in St. Louis to provide encryption solutions for the protection of desktop and laptop computers, smart phones, PDAs, and removable media storage devices, including CDs and memory sticks. Mobile Armor’s solutions secure stored data, now commonly called data at rest, on a computer, wireless device, or removable storage media or device.

The Data At Rest Tiger Team (DARTT), comprising 20 DOD components, 18 federal agencies, and NATO, has approved Mobile Armor’s software and hardware encryption products for full disk encryption (FDE), file encryption (FES), and integrated FDE/FES within all federal, state, and local government agencies.

DataArmor, Mobile Armor’s 32-bit pre-boot authentication, full-device encryption product ensures device data security with authentication technology and user-transparent data encryption. The company’s FileArmor centrally managed file and folder encryption extends endpoint data protection to removable media and portable data storage devices.

Following testing by the U.S. Army Technical Integration Center (TIC), Mobile Armor’s Web services-based centralized policy management tool and encryption protection solutions have been approved for the U.S. Army Information Assurance Approved Products List.

“The White House is increasing its focus on data at rest, as it has profound implications on national security,” explains Chand Vyas, chairman and chief executive officer of Mobile Armor.

Future trends

“There are governments that are building units, military units and intelligence units, to engage in information warfare,” explained Richard Clarke, former chief counter-terrorism adviser on the U.S. National Security Council and member of the Senior Executive Service, specializing in intelligence, cyber security, and counter-terrorism, in 2000. “They are developing capabilities, they are building units, and in some cases they seem to be doing reconnaissance on our computer networks.”

Technology companies, many with backing and assistance from government agencies and industry organizations, are continually advancing data security, the need for which will continue indefinitely.

Engineers at Phoenix International in Orange, Calif., as an example, are at work on a solution capable of rapidly sanitizing data stored on its hardware for two U.S. defense programs. They are using Flash drives in place of traditional hard drives in VME storage modules, providing clients the ability to quickly and completely destroy information stored on the drives in, for example, a military aircraft that has an emergency condition that requires an immediate landing in unfriendly territory.

Amos Deacon III, vice president of sales and marketing at Phoenix International, uses the example of the forced landing of a U.S. Navy EP-3 ELINT Maritime Patrol Aircraft on the Chinese Island of Hainan in April 2001. Sensitive information was gleaned from the aircraft’s data storage disks because the system lacked a sanitization method that would destroy the information. “They don’t want data to fall into the wrong hands,” acknowledges Deacon. “They want to be able to destroy data before that happens. Solid-state flash drives use various techniques to secure, erase, and sanitize data in seconds to achieve various DOD and NSA data-security levels.”

Removable media and drives are another popular method of securing classified data in combat or emergency situations. Ciprico’s Talon system, deployed in airborne data-acquisition missions, is a rugged, high-performance RAID storage system with a removable disk pack that contains up to 11 rotating disks. “Upon completion of a mission, the disk pack containing the mission data is physically removed from the aircraft and carried by hand to a secure ground station,” explains Ciprico’s Ascher. “It provides a quick, easy, and secure way to declassify the plane and move the data to a secure location to tightly control access to the information gathered on the mission.” This quick declassification ensures the critical information does not fall into unfriendly hands, who can then take the necessary defensive or offensive actions based on the information gathered, says Ascher.

Clients in the defense market are also opting for hardware data encryption to secure information. ”Multiple sources are asking for data storage systems that encrypt data as it is received, before it is written to disk,” says Deacon, describing a trend he has witnessed over the past six months. “Once classified data is written to disk, it cannot be left unsecured. If the media on which the classified data resides is left on an aircraft, for example, armed guards are required for security. This can become both expensive and inconvenient. If the information is encrypted before it gets to disk—a methodology that Phoenix engineers are incorporating into the company’s new RPC-12 RAID mass storage system—those measures are not needed; if the disk falls into the wrong hands, the encrypted information is no good to them.”

Several different levels of encryption exist. “We are working on hardware encryption that uses AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) 256, the most advanced algorithm available, and are embedding it into our hardware,” Deacon continues. “The NSA has determined that AES 256 is secure enough to protect classified information up to the Top Secret security level. In the past, a technique referred to as a Brute Force Attack was used to defeat a cryptographic scheme by trying a huge number of numeric key possibilities. With AES 256, it would take hundreds of supercomputers trying each and every single combination of characters years to unlock data on that system, by which time the data won’t be any good to them anyway.”

Security technologies defined

Cryptography: the process of encrypting and decrypting information using algorithms (ciphers) and one or more keys.

Encryption: the process of converting readable information (plain text) into unreadable data (cipher text) using a cipher and a key.

Cipher: algorithms that perform the encryption/decryption (example AES, 3DES).

Information provided by Nauman Arshad, technical product marketing manager for Network Centric Infrastructure Products at Curtiss-Wright Controls Embedded Computing.