Information warfare highlights one of the most distressing weaknesses of COTS

Information warfare highlights one of the most distressing weaknesses of COTS

By John McHale

Before the dawn of commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS)-based systems and even as recent as the Persian Gulf War, the U.S. military services and their allies did not have technological commonality. Incompatible computer systems were particularly troublesome because they slowed communications. A story circulated during the U.S. military action in Grenada that ground forces had to call in air support by using a telephone credit card for a long distance call to the states.

Not any more. Now U.S. military commanders can obtain aircraft reconnaissance imagery, analyze it, then use it to tell forces on land, at sea, or in the air in minutes where to deploy. Today`s forces accomplish these feats with state-of-the-art communications systems based largely on COTS technology. Now all the services share common communications networks and technology.

One problem — the increased commonality means increased vulnerability to information warfare. Today, more so than when military forces fielded custom-designed systems, people and countries unfriendly to the U.S. may be able to listen in and even participate in military operations by using cyberspace to spread disinformation.

One day soon Navy leaders might find their destroyers deployed to the wrong coordinates, and their planes bombing the wrong targets due to an enemy state, an individual cyber terrorist, or even a high-school hacker committing an act of information warfare on the U.S. military`s command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence (C4I) system.

"COTS products will provide the C4I-system commonality between our services, allowing joint interoperability and effective connectivity with our allies," says Ronald K. Newland a fellow engineer at Northrop Grumman`s Electronic Sensors and Systems Sector in Baltimore. "The irony is that while we become more interoperable, our vulnerability is rising in direct proportion to the level of commonality and COTS products used in the C4I systems. `Stovepipe` C4I legacy systems were generally useable only within the service that developed them and did not connect well with the Internet."

The United States is particularly vulnerable precisely because of its technological lead. "Forty percent of the world`s computers are in the U.S.," making not only the country`s military vulnerable but the infrastructure as well, says Rob Clyde, vice-president and general manager of the Axent Technologies Inc. security management business unit in American Fork, Utah. Clyde also is founder of Axent`s InfoSecurity SWAT team.

Military forces are not the only organizations that need information security. Banks, Wall Street, and the transportation industry, to name a few, all depend on secure information. Banks and security firms currently spend the most time and energy on information security with the military close behind, Clyde says.

Information superiority

"What information superiority really means is being the one most dependent on computer and communications technology for combat success, Newland says. "Because of this, any military in our position cannot afford to lose C4I connectivity or data integrity. Information warfare attacks can be initiated and conducted from a distance, via radio-frequency links or international communications (commercial) networks, with no physical intrusion beyond the perpetrator`s own borders," he continues.

"The much-publicized antics of two very talented teenage hackers who accessed U.S. Air Force information systems should serve as a strong wake-up call," Newland warns.

Loosely defined, information warfare operations involve "any action to deny, exploit, corrupt, or destroy the enemy`s information and its functions; protecting ourselves against those actions; and exploiting our own military information functions," Newland explains. "In other words, do it to them, but don`t let them do it to you. This concept is all well and good, assuming that you are the biggest dog on the block. Unfortunately, [information warfare] is a sort of `Charles Atlas in a pill,` an immediate equalizer."

Superpowers should not assume information dominance and information superiority simply because they are superpowers, Newland warns. "Even the smallest, poorest country can find the resources to fund intrusions, computer viruses, logic bombs, and system manipulations in the global Internet to which the U.S. military`s C4I structure is not only attached but embedded," he says.

Newland says he fears that future cyber attacks may not even originate in a sovereign country but come from "techno-terrorists" and "transnational religious fanatics."

In such a scenario, "well-paid mercenaries insert the latest virus or logic bomb into our principal operating nets, causing disruption to our ability to recall, marshal, deploy, employ, control, and task our rapid deployment forces," Newland explains.

Mercenaries are not the only ones to fear, Clyde warns. "You don`t have to be a guru anymore. Any body can download [hacker] shareware off the Web and hack in by the click of a mouse," Clyde says.

People can find the hacking tools they need with a simple Internet search, he adds.

Hacker groups such as the Cult of the Dead Cow have distributed a freeware package called Back Orifice, which makes it easy for computer intruders to hijack Windows-based PCs connected to the Internet, says Tim McCormick, vice president of corporate marketing Internet Security Systems (ISS) in Atlanta.

McCormick`s research team at ISS, called X-Force, recently sent one of its members to the annual hacker convention, DefCon, in Las Vegas, to check up on Back Orifice, he says. During a demonstration given by Back Orifice`s creators, "they threw out about five copies of the shareware to the audience and our guy jumped over two rows to get a copy. Then our X-force team spent the weekend breaking down the software and on Monday morning we had a product out to protect against Back Orifice," McCormick says.

"We`re seeing hacker programs merging with the techniques used to spread computer viruses," McCormick says. The hackers will break into a system, observe how the outside world communicates with that system, and use that means to enter the system in the future and wreak havoc. The hackers can piggyback on an e-mail, the way viruses do, McCormick explains. Back Orifice is like that, he adds.

Enemy states and hackers can also wreak havoc on the government`s publicly available Web sites, Clyde says. In Kosovo the Yugoslav army clogged up the NATO site and created heavy traffic, effectively slowing down NATO operations that day, he adds.

The U.S. military has classified Web sites that do a good job of protecting classified information, but the unclassified public sites need to be better protected and monitored, says David Hollis, director of government sales at Secure Computing in San Jose, Calif. Enemy states can gather all the unclassified intelligence, aggregate it, and get a pretty good idea of what is classified.

"In the future, if we are in a crisis situation with an international adversary, as was the case during the Gulf War, it is likely that they would target our domestic transportation systems to disrupt mobilization efforts, Newland says.

"Following this, they may attempt to gain access to logistics nets in an effort to cause misrouting of supplies or even shipment of the wrong supplies," he continues. "Once the forces were fully in theater, it could be expected that the operations nets and battle-management nets would be attacked to change tasking orders, delete missions, create false tasking orders and relocate entire units. Once operations were underway, the adversary would probably attempt to influence the engagement nets with false targeting data and a heavy communications-jamming effort. After combat operations begin, an adversary could enter the logistics or medical nets to alter patient information such as blood types or to cause delays in the delivery of medical supplies.

"This scenario would have been much more difficult during Desert Storm, but a similar conflict today would find our high-tech, seamless systems much more vulnerable because they are COTS and much less stovepiped," Newland warns.

Newland uses as an example the World Wide Military Command and Control System used by the U.S. Air Force, which has since been replaced by the Global Command and Control System. "The very characteristics that made them difficult to work with in joint operations also made them secure and relatively safe to use. Now the C4I capability of every service, being common and connected to one another as well as to the outside world, is accessible and incredibly vulnerable."

The best offense is a good defense

Newland believes the best way to prevent these enemy attacks is to employ tactical deception, which is "the idea of gaining the upper hand on your adversary by getting him to believe what you wish him to believe, causing him to act and respond as you wish him to, he says.

"Most people tend to think of deception as an offensive measure," Newland says. "However, history suggests that we will only be fighting from a defensive posture at the outset of any hostilities. As a result, we should have a full suite of defensive measures in place that are above and beyond the capabilities of firewalls to protect our combat C4I systems and to provide what is needed for an effective transition to offensive information operations," he says.

The Russians, for example, call tactical deception "maskarova", a term that focuses on the defensive aspects of the concept. "This is the art of making a jet aircraft look like a pine tree or a tank regiment look like a lake," Newland says.

It is another form of disinformation that the U.S. military must now take to the cyber-battlefield of today Newland says.

Newland and experts at the Air Force Research Laboratory Information Directorate in Rome, N.Y., are working on implementing a tactical deception concept called Sleeping Beauty. This approach involves techniques that Newland says "could allow an adversary to believe he has entered networks/systems successfully and allow him to look at bogus data that he could manipulate or corrupt to his heart`s content. Meanwhile the real databases or networks would perform their intended tasks uninterrupted with viable intelligence and other combat-essential data."

Firewalls are only part of the answer when it comes to defensive information warfare, Newland says. If the U.S. military can control what information the enemy gets and fool him into believing he has succeeded, then "we will have achieved the paramount goal of [Information Warfare]: influencing the enemy`s perceptions to suit our aims and cause him to act in a more predictable manner."

Industry`s answers

Implementing an information security system is similar to installing a security system in the home, ISS`s McCormick says.

When a home system first activates, it performs a scan assessment of the house — checking to see if windows are shut and if doors are locked. Information security systems work the same way, telling the users where the holes are in the system and how to plug them.

For this type of risk assessment, ISS offers vulnerability management solutions — Internet Scanner, System Scanner, and Database Scanner. The automated and continuous scans are to ensure user activity is in compliance with established security policies and provide detailed corrective actions, prioritized security risks, and a range of reports for the identification and elimination of security holes.

Once the software plugs holes it creates a firewall — the first line of defense against information warfare.

Firewalls

A Firewall acts as a gate, preventing unauthorized access. While Firewalls offer perimeter and access controls, internal, remote, and even authenticated users can attempt probing, misuse, or malicious acts, Axent officials explain. Firewalls do not monitor authorized users` actions — once in, anything goes. Firewalls control perimeter access and therefore do not address internal threats. Firewalls must guarantee some degree of access, which may allow for vulnerability probing, they say.

Firewalls also do not prevent the use of unauthorized or unsecured modems as means to enter or leave a network.

Many basic firewalls can be overcome — these are called packet-firewalls, Axent`s Clyde says. Most hackers can break through these, therefore application-level firewalls are necessary for complete protection, he adds.

An application firewall uses proxies to examine and relay packets, Secure Computing officials explain. Application-level firewalls isolate activity between the two network interfaces, external and internal, by shutting off all direct communication between the two network interfaces. Network packets never pass between these two interfaces. Instead, application data transfers in a sanitized form between the opposite sides of the gateway. As the gateway examines inbound and outbound packets, internal users do not have the ability to access unauthorized services that might subvert security.

Axent offers the Raptor Firewall, which provides tight integration with Microsoft Windows NT using the Microsoft Management Console-based Raptor Management Console for flexible scaleable enterprise management. In addition, the Raptor Firewall provides native high-availability support using Microsoft Cluster Server.

For firewall protection Secure computing offers Sidewinder, an application-level security gateway that uses Secure Computing`s Type Enforcement security and offers protection for e-mail, Java, and the Web, says Denny Netland, product marketing manager for Sidewinder at Secure Computing. As a network security gateway, Sidewinder provides additional technologies and filters beyond traditional firewall capabilities. This allows for a safe connection to an untrusted network.

Type Enforcement controls what users can do on the system and which files a specific process running on the system can access. It protects the Sidewinder and the network from intruders by preventing anyone from taking over the system and accessing crucial files or doing other damage. It also allows the system to keep information on the internal and external networks completely separate until the Sidewinder allows the data to transfer from one network to the other. Since Type Enforcement is implemented at the UNIX kernel level, it cannot be circumvented, Secure Computing officials claim.

Sidewinder was originality developed by Secure Computing for the U.S. National Security Agency, Secure Computing`s Hollis says.

However, firewalls, like locking the doors and windows for a home security system, are not always enough to stop an intruder; sometimes motion detectors are necessary to sense an intruder and alert authorities, McCormick explains. For this same reason in information security, firewalls need intrusion-detection tools, he says.

McCormick and his colleagues at ISS offer RealSecure, an integrated network- and host-based intrusion-detection and response system. This maximum level of around-the-clock surveillance extends across the system, enabling administrators to automatically monitor network traffic and host logs, detect and respond to suspicious activity, and intercept and respond to internal or external host and network abuse before intruders can compromise the systems.

Axent`s experts designed NetProwler, which complements firewalls by analyzing the authorized traffic and attempting to exploit known vulnerabilities. Since NetProwler passively monitors network sessions, it does not influence network or application performance — thus it can support perimeter and internal deployment. Lastly, NetProwler can harden firewalls to prevent subsequent entry by an attacker.

Network security is more than firewalls, encryption, and authentication devices; it is complete, security management, McCormick says. At its best, it is a flexible process that provides constant feedback on the status of defenses, recognizes attacks and misuse, and responds with appropriate reconfigurations and countermeasures.

ISS` decision-support solution, SAFEsuite Decisions, provides information by automating the collection, integration, analysis, and reporting of enterprise-wide security information from several different sources and locations including integrated data from the ISS intrusion- and vulnerability-detection systems, as well as third-party security products such as firewalls.

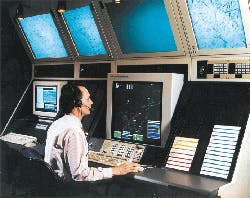

Photograph courtesy of Northrop Grumman Corp.