By Ben Ames

MOORESTOWN, N.J. — Modern warfare relies on the precision strike, and the ability to plant small bands of special forces deep in foreign territory. That means Navy ships must cruise dangerously close to shore, within range of the latest missiles.

One solution to the problem is the SPY-1D(V) radar, an upgrade to the Aegis Weapon System.

"It's designed for the littoral environment, where you need a quick reaction to cruise missiles and other increased threats," says Chris Myers, vice president of business development, Lockheed Martin Naval Electronics & Surveillance Systems, in Moorestown, N.J. "It has the capability to pick out targets from the clutter of land."

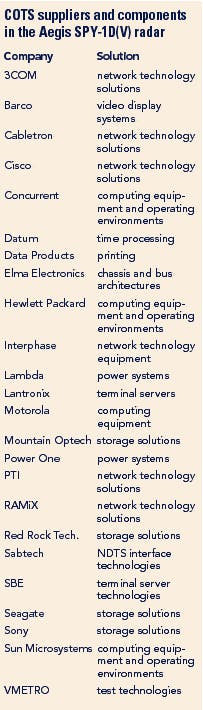

The Lockheed Martin SPY-1D(V) does that through improved signal processing, and an open computer architecture that uses commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) components.

The SPY-1D(V) radar uses commercial components to help the Aegis Weapon System detect missiles close to shore.

null

The open architecture design will ease installation and upgrades, Myers says. In fact, maintenance is easier for this seventh-generation Aegis system than its predecessor since engineers built it to be "very sailor-friendly," by running a long time between maintenance opportunities.

Navy engineers have installed the system on the Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer USS Pinckney (DDG 91), which begins sea trials in August and is due for commissioning in May, 2004. In April, the ship tracked live, airborne targets in shipboard testing of the system.

"As the threat has increased, our detection ability has paced that," Myers says. "There's a whole slew of ballistic and cruise missiles proliferating in the world, so we have to negate those threats."

Visually, the new radar looks like an octagonal metal plate bolted to the superstructure of the ship. Under the plate is the antenna for a phased-array radar that electronically steers its beam through space without a mechanical rotator. There are four antennas on each ship, providing 360-degree horizontal coverage and a dome of vertical coverage from azimuth to wave tops. The complete effect is like a salad bowl of radar coverage placed over the vessel.

"The other good thing about phased array is that you can concentrate energy where you need it," Myers says. That way, an operator can boost the range and resolution in a particular direction without blinding the ship to threats from another side.

The Aegis system, which is part of the Burke-class destroyers and Ticonderoga-class cruisers, relies on a separate sonar system to track undersea threats like mines, torpedoes, and submarines. The complete package can simultaneously follow land, air, and undersea threats and attacks. The SPY-1A and -1B radar classes are designed for the cruisers, while the -1D class is for the destroyers. The letter "v" in SPY-1D(V) means variant.

U.S. Navy leaders have installed previous Aegis systems on 65 ships, and say they plan to buy 24 more. Aegis — the mythological name of the shield belonging to the Greek god Zeus — is also the primary tracking system for navies in Japan, Spain, Norway, and South Korea.

Lockheed Martin engineers have also released the SPY-1F Aegis upgrade, now being tested by the Royal Norwegian Navy. That primarily defensive system is designed to work with a wide range of vessels, from corvettes to frigates to aircraft carriers.

The next generation of Aegis radar will be an active, solid-state, phased array called the SBAR (s-band advanced radar), Myers says. Instead of relying on one centralized transmit/receive module, as the SPY-1D(V) does, it will deploy many separate modules in each of the four antennas on a ship. That distributed design will enable greater range and performance, he says. Lockheed Martin engineers demonstrated a prototype in May for Navy officials.

null