Information technology is key to Air Force 2020

As Air Force leaders look to the future, they are examining how information dominance and real-time shared situational awareness are critical to the challenges of four kinds of military operations: traditional, regular, catastrophic, and disruptive.

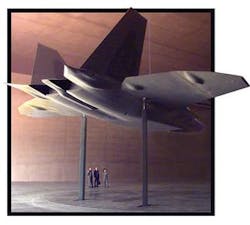

The U.S. Air Force is laying the groundwork to complete its transition from an industrial-age fighting force to an information-age force. By the year 2020, information will even be far more important to the Air Force than bombs, missiles, jet engines, and stealth aircraft. The command of information, as envisioned for the year 2020, in many ways will render obsolete the “brute-force” approach of overwhelming an enemy with vast numbers of jets, bombs, and missiles.

The Air Force 2020 electronics and optoelectronics technology roadmap envisions a wide array of networked sensors, automated systems such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), sophisticated information processing, high-speed data storage and retrieval, directed-energy communications and weapons, futuristic graphic displays, and perhaps most important, an Internet-like “infosphere” with the ability to make pertinent information available immediately to the people who need it most.

At the core of this Vision 2020 are information dominance and real-time shared situational awareness. These capabilities are the chief enablers of the Air Force’s transformational plan that involves global reach, the ability to strike anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice, and a penetrating knowledge of the enemy’s situation and resources relative to those of the Air Force, its fellow military services, and its allies.

“We will establish an ability to exchange information among all our platforms - manned and unmanned aircraft, space platforms, ground-based operating centers that control our forces and our support activities, and literally to every airman,” explains John Gilligan, chief information officer of the Air Force, who is based at the Pentagon. “Every one of our airmen and our assets becomes an IP address, all will be connected on a relatively high-speed network. We overlay the Internet paradigm on our Air Force, and everyone and everything becomes an IP-addressable node.” IP stands for Internet Protocol.

An evolving plan

The Air Force 2020 vision has evolved substantially over the past several years. While much of the plan has remained consistent - global reach, undisputed air power, and reliable knowledge of friendly and enemy forces - much has changed, such as the overriding emphasis on information dominance and network-centric warfare.

The Air Force’s third and shortest outline for its structure for the 21st century, “Global Vigilance, Reach and Power,” reaffirmed the concept of 10 aerospace expeditionary forces (AEF), two constantly on alert as a “911” force, each able to deploy within 48 hours, a task force providing intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR), and command and control of aerospace forces over an area roughly half the size of Texas. This document, published in 2000, and more commonly referred to as Vision 2020, is a subset of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) overarching Joint Vision 2020. The AEF can provide air superiority while striking some 200 targets per day. One AEF can surge to provide these capabilities 24 hours a day. “More AEFs can be added, expanding the space we can control and contributing to our ability to transition rapidly from contingency operations to major theater war,” the document states.

Fifteen months after its publication, however, “911” took on a whole new meaning and the Air Force had to engage simultaneously in two swift, consecutive war zones in Southwest Asia, gather lessons learned in near-real time, and assess what these new threats would mean two decades later. These threats involve a new, shadowy, stateless enemy and a new kind of warfare that blends traditional force-on-force and nation seizure with antiterrorism and intensely focused ISR.

Dr. Christopher J. Bowie, deputy director of Air Force Strategic Planning, notes Vision 2020’s broad reference to global reach, power, and vision originally was put forth in 1990 as the half-century Cold War was coming to an end and the primary adversary was the Soviet Union, with conventional and nuclear forces similar to America’s was breaking apart.

“Since 9/11, it is really the degree of emphasis that has changed, but the broad capabilities have remained the same,” Bowie says. The U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) is directing the Air Force to examine the challenges of four different kinds of military operations: traditional, regular, catastrophic, and disruptive.

U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld “has said we need to place a greater emphasis on the latter three than to the traditional,” Bowie says.

The original Vision also was based on experiences from only one and decidedly one-sided air war in more than a quarter of a century, during which entire generations of aircraft have retired, been introduced, and grown old. Since the original Vision, Space-based assets matured substantially, the network-centric battlespace came closer to reality, and a near total conversion to precision-guided weaponry has essentially made all previous air warfare tactics, techniques, and procedures obsolete. Nonetheless, the original Vision set the Air Force on the right path, says Col. Allison Hickey, assistant deputy director of Air Force strategic planning.

“Vision 2020 had us well prepared for what we have done, including how we will deploy and reset forces. It also dealt with information and global deployment, so we are just taking that document and moving forward as we learn lessons and apply real-time solutions. We are taking it to the next step and applying it to our transformation flight plan and other future capabilities for technology in the 2025 time frame,” Hickey says.

“We’ve done a lot of work in the last few years to consider what our role as an Air Force is, especially with respect to the irregular and disruptive battles. We played our last future capability game, looking at the 2020 time frame, with a strategic environment that was very much irregular, with disruptive technologies and so on. So we gained a lot of insight into both our strengths and our challenges. Part of doing those kinds of efforts, and those hard looks at yourself, both from the real work and gaming aspects, is to apply those to an existing plan and adapt it. Which is how we have grown from the 2020 document to our future force structure discussions.”

Information-age warfare

These discussions often revolve around a readily available body of information based on the position and status of every Air Force resource - personnel, aircraft, vehicles, computers, and other supplies. “If all our resources are IP-addressable nodes, we envision an information spec that allows us to give our airmen access to the information they need to make decisions,” Gilligan explains.

To do this, Air Force officials will rely on commercial technology as much as possible, and develop new technologies only when those necessary are not available on the commercial market. “In the main, for information technology, we are depending and relying on the commercial technology base,” Gilligan says.

“What is happening in the commercial market is addressing most of our needs in terms of connectivity, from copper to wireless,” he says. “We are fielding a lot of fiber and in fact most of our bases we already have a fiberoptic backbone and we will continue to invest with that. We see an exciting possibility to augment fiber with wireless networks. On aircraft flight lines, for example, there are not a lot of people and there is a lot of physical space. Wireless is an attractive solution, but more for fixed bases in the United States than when we deploy.”

Although commercial technology has become to military systems designers, sometimes this technology does not go far enough for military users. “The commercial sector has not been as robust as we would like for information and information protection,” explains James B. Engle, deputy assistant secretary of the Air Force for science, technology, and engineering. “DOD is much more serious about it, and we are putting investment into it. In encryption and information security, we are taking these technologies much more seriously than the commercial sector.”

Military technology developers often must choose between off-the-shelf technology, or technology custom-designed at government expense. Increasingly, however, military planners are trying to find a compromise between these two alternatives. “We want to take the commercial sector’s contribution and rework it to meet our needs,” Engle says. “We could tighten up some of the algorithms that the commercial sector produces, and that will be a growing area for us.”

Another area in which commercial technology can fall short of military needs is information search and retrieval. Although Internet-search capability available on the commercial market forms a solid foundation, Air Force leaders are looking for more, and are interested in developing some unique capabilities.

“There is a set of information-handling and management technologies we are looking for as we move forward that take us from the ability to do a Google search,” Gilligan explains. “We want predefined information so when we do a search to support a particular decision, we have already defined authoritative sources, and already have algorithms to pull and refine data, with security and timeliness, to meet the needs of that decision.”

In addition, Gilligan says Air Force leaders want to develop information-search capability that is as automated as possible “so the human is not overwhelmed” either with too much information, or with the need to manipulate data. Thus far the commercial market is offering some encouraging capabilities,” he says.

“We are seeing some of the fundamental tools that are being matured, technology and processes and how to better manage information - the science of how we define the precision, the security characteristics, the authenticity and perishability, and how we attach that to information.”

Information security will have tremendous importance as Air Force leaders connect increasing numbers of assets and personnel. “First we see an overlay to the net-centric environment, with airmen and assets at IP nodes,” Gilligan explains. “We need technology to have robust identificaton of people and network assets, because increasingly there will be connectivity across the network where it will be important to know: is this really the commander who is making this command?”

Not only will the reliability of user identities be crucial for Air Force operations of the future, but the reliability of increasingly complex software programs also is at the forefront of planners’ minds. “We need more highly reliable code, so we have software with greater assurance of correctness,” Gilligan says. “We also want to be able to make sure that software has not been tampered with or reverse engineered.”

The future F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a case in point, Engle says. “Collectively, the entire platform of software and sustainability of the F-35, you are probably approaching seven million lines of code. The commercial sector has not gotten to that degree of complexity. Software producibility will grow from a government perspective, and we will find some areas that the commercial sector is not addressing.”

The issues of writing, testing, and maintaining such a level of software complexity in many ways is new technological territory, and Air Force officials have their work cut out for them. “How to take that level of complexity to a high level of assurance will take some work on the part of the DOD,” Engle says.

“What we don’t know is once we write 3.5 million lines of code, how do we effectively implement and integrate that into a complex system like the F-35 that has hundreds of subcontractors?” Engle says. “How do you take that code and test that software to get high assurance of reliability that it won’t crash at some unknown point?”

Dynamic war planning

The 2004 Future Capabilities Game last January at the Air Force Wargaming Institute at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., was the first in a new “leaner, meaner” biannual approach to testing Rumsfeld’s four future Air Force capabilities from a more dynamic, responsive, strategic planning perspective. Involving fewer people than previous war games, it brought together planning strategists from all the U.S. services and major U.S. allies to do red and blue team battles using Air Force baseline predictions for its make-up in 2020, then running a second scenario using more “forward-leaning” capabilities not yet implemented but under development, such as unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVS) and directed-energy weapons.

These “what if” scenarios offered a clear vision of how changes in weaponry and tactics could influence outcomes and where the Air Force should concentrate its research, development, and procurement spending. The war game, however, was only one tool contributing to the new future vision. Real war has offered another perspective.

“The lessons we’ve learned certainly have honed us in on certain areas in the 2020 Vision document. We’ve seen a great emphasis from everyone on the ISR element and tightening the kill chain and maintaining information flow superiority,” Hickey says. “So now we look at what we need to put more pressure on increased capabilities with fewer platforms, both manned and unmanned. And with the focus on joint capability investment, we’re looking at what systems we will need in the future and what our coalition and joint partners need from us. We are starting to see things from that joint perspective and the dollars are following that eyesight.”

Bowie says Air Force investments can be broken into three broad areas: combat forces, headquarters training bases, and joint enabling forces.

“That’s where C4ISR, weather satellites, air-breathing reconnaissance, mobility accesses, and refueling aircraft come into play. What you see historically is that investment in the 1960s was about 33 percent for joint enabling forces. Today that percentage stands at 45, almost half the Air Force budget,” Bowie says. “Looking to the future, out to 2020-2025, we see that trend continuing, with half or more of Air Force spending going into joint enabling capabilities,” he says. “As your force gets smaller and the mix of investments changes to more joint enabling capability, that will drive a change in your active/reserve balance, as well. The Air Force already has a very highly integrated force, using our Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve component very well. We see that continuing in the future.

“What you see since the Gulf War in ’91 has been a steady increase in the use of UAVs, both in numbers and capabilities, but the key aspect is their persistence,” Bowie says. “With Global Hawk, flight time is something like 36 hours, which gives you tremendous leverage. It is the kind of thing that is very difficult to do with a manned platform. In the game, we also looked at using UAVs as communications links, with both space and air, to form a network, which made you far more redundant and far more difficult to block. The Air Force is excited about the potential offered by UAVs and will continue to invest in that area.”

Hickey says the AEF concept of Vision 2020 looked at another evolution relatively new to the Air Force: the battlefield airman concept, linking special forces on the ground with airborne assets overhead.

“It is really looking to see how the airmen we have on the ground, who are increasingly operating in areas we don’t normally think of airmen operating in, should be equipped, how we connect them with all the real-time capabilities we’ve often thought of in terms of platforms and force-on-force. Now we want to make sure we have armed and prepared them well for the very valuable role they have,” she adds. “We’re also working an initiative under the space-cadre element. You can’t do the C4ISR mission independent of the rest of Air Force operations. The integration of space, air, and cyber or information common elements is key to the future. Finding, identifying, tracking, fixing and striking a target are all part of that.

“There also is a lot of work being done in an area not much heard from before 9/1: directed energy both from defensive and offensive capabilities. We have a master plan ranging everywhere from nonlethal to lethal, with broad applications. By the 2025 time frame, I think the science will be there to do the same kind of major shift that programs did for us in the 1990s - area denial with nonlethal effects, a whole family of capabilities in the directed-energy portfolio.”

Directed energy

One of the most exciting technology areas that Air Force leaders will pursue over the next two decades is directed energy - primarily lasers for communications and weapons, but also high-power microwaves, and sonic weapons. “The real game changer, and a real breakthrough, is directed energy,” Engle says.

Lasers are among the chief enabling technologies of the future Air Force Transformational Satellite Communications program, which will provide high-speed communications links between satellites to create an orbiting tactical network for information retrieval called the Global Grid.

In addition, future weapons-grade lasers, coupled with satellite laser relays, might enable a future capability to strike any target anywhere on Earth within seconds of detection. “If you take the Global Grid, and information is flowing coherently with some assurance, you can overlay an engagement at the speed of light,” Engle says. “You would have a different battlefield than you have today.”

Engle outlines a scenario in which a land-based high-power laser weapon and a global network of satellite-based mirrors are standing by for intelligence information on high-value targets located anywhere in the world. If sensors detect a mobile missile launcher in a remote area, they could relay its coordinates to the satellite mirrors that could quickly align to relay the laser weapon to the target.

This capability could reduce the time it takes to scramble bombers or other assets to engage high-value targets from hours - or even days - to only a few minutes. “With directed energy, you can condense the time to engage to seconds,” Engle says. We would go Mach a million rather than Mach 2. If you have high-energy laser weapons and could stand off hundreds of miles, you could stand outside the enemy’s defenses, engage from longer ranges, and still get an engagement the time of about a minute.”

Nanotechnology

Over the course of the next two decades, information dominance, network-centric warfare, unmanned aerial vehicles, and directed-energy weapons are expected to come to the forefront, yet other technologies are likely to burst onto the scene for military applications toward the year 2020, although their pace of development is difficult to predict.

“There is exciting work in nanosciences that will enable a lot of materials work, as well as electronics and information transfer,” Engle says. “But, practically, there is not a lot of nanotechnology right now, and not a lot of nano engineering; that is yet to come.”

Nanotechnology, which involves sophisticated machines too tiny to detect with the human eye, has broad promise for sensors, materials, communications, and direct military attack. One area Air Force officials are eyeing for nanotechnology is manipulating explosive materials at the atomic level, Engle says.

“We want kinetic energy to do exactly what we want to that target. Sometimes we don’t want to destroy a target, but just turn it off for a period of time,” he says. “We want to have an understanding of explosives mixtures at the atomic level, so we could wrap energetic material around atoms of tungsten and control the speed of the explosion as it spreads out from its source, and steer the explosion.”