By J.R. Wilson

Cooperative Engagement Capability — otherwise known as CEC — seeks to blend sensor information from many different platforms and make them widely available, even to counter-terrorism infiltration teams such as Special Forces and forward-deployed reconnaissance forces.

The September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York and on the Pentagon in Washington has brought a new urgency to developing and fielding the U.S. Navy-sponsored joint Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), an effort to bring all of the sensors available in a battle theater together and provide combatants at sea, in the air, and on the ground with a unified sensor picture.

The CEC seeks to blend information from many different sensors — particularly radar sites. In this way, the CEC network can overlay sketchy or incomplete information from a variety of sensors to create a complete picture that weapons platforms can access and use for targeting.

This kind of capability becomes more crucial with each passing year, as the job of detecting ever-more-sophisticated threats progressively becomes a more difficult challenge. Seventy nations deploy anti-ship cruise missiles today, and an emerging threat looms from land attack cruise missiles. U.S. defense experts see CEC as part of a significant tactical shift away from the old approach of platform-centric battle using single sensor tracks and toward a force-centric strategy involving multi-sensor measurement fusion.

For now, this is primarily designed as an enhanced air defense system, but planners expect it to evolve beyond that in the coming years.

The U.S Navy E-2C Hawkeye radar aircraft (right) is a primary CEC platform.

"The character of the system changes when you do sensor netting in the context of ground warfare and other applications, but it is quite a different animal from air defense, which is the focus right now," says Gifford Clegg, director of advanced programs at CEC prime contractor Raytheon Joint Sensor Networking in St. Petersburg, Fla. "That is in concept phase and development is probably way out on the horizon, although, given the world situation, it's hard to say what will happen tomorrow."

Another major effort at the moment is to upgrade system elements — currently built around early 1990s technology — and in the process dramatically decrease size, weight, and cost.

"What we're doing now is a technology refresh, upgrading all the processor cards to faster processors," Clegg says. "We're going to take a 3,000-pound suite that goes on a ship, including the antenna, and cut it in half in both size and weight — which also equates to about a 50 percent reduction in cost."

The processor change involves moving from Motorola 68040s to PowerPCs. That also will enable designers to go from 19 separate processing cards to two for a standard shipset.

While the Navy is the lead service on CEC, top military leaders expect the Navy to bring U.S. Army and Air Force sensors, as well as weapons platforms, into the fold. That includes recently completed efforts to integrate two CEC equipment sets into an Army Patriot anti-missile system command post and a simulation that mates CEC with an Air Force E-3A Airborne Warning And Control System (AWACS) aircraft.

"The idea is to do an engage-on-remote, using a Navy CEC capability to help engage a target outside the range of the Patriot radar," Clegg says. "The PAC-3 [Patriot Advanced Capabilities, Phase 3] missile has significantly longer legs than the radar can reach. So CEC enables the use of the full kinematic range of the missile," Clegg says.

As to the Air Force effort, "the goal was to show the benefits that AWACS provides to the CEC net and the benefits the CEC net could provide to AWACS," he says. "They used a typical Northeast Asian scenario, with a mixture of high-performance aircraft and missiles. It definitely showed that, where AWACS couldn't necessarily see all threats all the time, the Patriot filled in the cracks using CEC."

In the simulation, the AWACS crew vectored four F-15 jet fighters (with actual pilots on simulators) to their targets using the combined CEC track.

The next step for Army and Air Force CEC managers is engineering development, Clegg says. Officials from both services should have a clearer idea of how they will proceed with CEC development and possible deployment by mid 2002, he says. Engineering development "will take CEC hardware, put it on an AWACS and do some testing," Clegg says. After that, Air Force leaders may buy CEC hardware to install on about 30 AWACS airplanes during a five- or six-year period, during scheduled maintenance and the Block 40/45 upgrade.

Raytheon experts also are working with Army's Patriot program office to put together an advanced-development plan involving CEC, with hopes of starting in 2003, he says. "CEC would only go on those Patriot batteries that will receive PAC-3, probably about 40 systems [half the current number of batteries]. That probably also would be about a five-year period, beginning in '03. Of course, a lot of these schedules could change and may be accelerated quickly due to what happened on September 11," he says.

CEC also is to be part of the international Medium Extended Air Defense System (MEADS), another new effort still in development and under review.

The new reduced size of the CEC package will operate from 110-volt, 60-Hz power sources, so there are no special power requirements. In addition, the current 800-pound airborne unit already has been mounted in a hard shelter on the back of a Humvee for the Army, which also will be getting a significantly smaller unit in the future.

CEC also has the TPS-59 Marine Corps air surveillance radar. Rather than mounting the airborne CEC suite on a Humvee, Marine Corps leaders prefer to repackage it into transit cases, which they then set up in their command centers.

Special Forces, intelligence agents, forward-deployed reconnaissance forces, and other units that do not contribute data to the CEC — which undoubtedly will be essential cogs in the developing U.S. counter-terrorism machinery — will be able to make use of CEC information because they can receive the resulting fused picture of the battlespace, experts say.

Military leaders want the capability "to export relatively high-precision track information to some user who may be on a low bandwidth channel and not part of CEC at all," says Tony Gecan, a Raytheon "Engineering Fellow" working on the CEC program. "We could send it on a JTIDS [Joint Tactical Information Distribution System] Link 16 track, for example, conceivably on Link 11, or the new NATO Link 22 version of Link 11. All that is being looked at. Those datalinks are encrypted and this is strictly an export mode," he says. As a result unauthorized users or computer hackers would be unable to come into the system.

CEC also is to boost the capability of theater ballistic missile defense (TBMD) by providing a continuous fire-control quality track on incoming missiles from acquisition through destruction, experts say.

Although each CEC unit can maintain track only for part of the missile's flight, the CEC's ability to fuze all incoming data can provide a continuous composite track. This enables downrange elements to detect the target earlier than they can today, and maintain the target's track longer than is currently possible.

The resulting additional capability will provide defending ships and anti-missile batteries with far more time and space than they have now in which to engage theater ballistic missiles. This is considered especially important to successfully developing the SM-2 Block IVA missile at about the same time as the CEC is ready for deployment. The SM-2 Block IVA is the upgraded TBMD and Anti-Air Warfare multi-role Navy Standard Missile from Raytheon Missile Systems in Tucson, Ariz., which is expected to enter service in 2003.

New ship integrationDefense experts consider CEC to be critical to the success of the planned U.S. Navy DD 21 Zumwalt-class multimission destroyer. The DD 21 will have a smaller number of crewmembers than do today's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. DD 21, which is set to enter service around 2011, will have a complement of about 95 — a reduction of more than 70 percent from current surface combatants.Research programs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., have shown that integrating additional commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) sensors — infrared, sonar, and an electronic countermeasures (ECM) suite — into existing integrated radar systems will enable large numbers of minimally manned, minimally combat-capable — but also less expensive — ships to perform as one fighting "pod".

This networking of sensors, fire control, and command-and-control across several different ships is key to making Network Centric Warfare a reality.

The CEC system is to blend information from several different sensors so the composite picture is far better than the simple sum of the sensor data.

The DD 21 is currently under competition from two teams of contractors. Leading the first competitor, also called the Blue Team, is the General Dynamics Bath Iron Works company in Bath, Me. On the Bath Iron Works team is Lockheed Martin Naval Electronics & Surveillance Systems in Baltimore as ship systems integrator. Leading the Gold Team is the Northrop Grumman Litton Shipbuilding company in Pascagoula, Miss., with Raytheon and Boeing. A down select originally planned for this past Spring was delayed until fall pending further reviews by the office of the secretary of defense and others. Gecan says network enhancement is a primary goal of the current phase of development.

"Up to now, we've done radars and IFF [identification, friend or foe] and we're trying to add new sensors, such as AN/SPQ-9B high-resolution radar. We're also beginning to look at the inclusion of electronic surveillance gear," Gecan says. "When you hear someone out there, you can find a bearing to their location, but also get information on the signal that can help identify the source, basically deducing that from the kind of emitters we hear coming off the target.

Another planned enhancement, Gecan explains, "is increasing the throughput rate by 2.5 times, which means 2.5 times more data than at our highest present rate. In the OPEVAL [operational evaluation phase], we demonstrated networks that were typically 10 or 11 nodes. We are working with the network-scheduling mechanisms so we can do considerably larger sizes. We'd like to get to the point where we can handle on the order of 100-plus nodes."

OPEVAL involved a three-week testing cycle in May and June, conducted along the Atlantic Coast and in the Caribbean with six CEC-equipped ships and one CEC-equipped E-2C carrier-based Hawkeye radar-surveillance/early-warning aircraft. Supporting these platforms were two non-CEC ships, fleet aircraft squadrons, and several different land-based test sites.

The evaluation included several different scenarios and live missile firings that, combined with the February 2001 technical evaluation (TECHEVAL), put the system through a full retinue of wartime conditions, including several hostile threats, difficult tracking scenarios, and extensive jamming.

Security concernsA major concern for a system of integrated sensors and platforms operating throughout a battle theater is security."The Cooperative Engagement Capability program incorporates a secure network communications terminal known as the Data Distribution System (DDS)," says Capt. Dan Busch, the Navy's CEC program manager at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) in Arlington, Va. "The DDS has been a segment of the CEC program since inception and was the means of communicating sensor measurements and track data between CEC participants during the recent OPEVAL. The DDS uses Communications Security (COMSEC) and Transmission Security (TRANSEC) to assure data security. Currently there are two configurations of DDS being supplied by Raytheon. The AN/USG-2 is the CEC terminal that is installed on ships and at various land-based test sites. The AN/USG-3 is an airborne configuration of the AN/USG-2 and is currently installed on E-2C and P-3 aircraft."

The DDS provides direct line-of-sight communication (transmit, receive, and scheduling) with other AN/USG-2 — or Cooperative Engagement Transmission Processing Set (CETPS) — units, primarily on C-band with full encrypt and high anti-jam operations. That can be extended to over-the-horizon via airborne and shipboard relays.

While CEC does not address the general communications needs of the military in combat, its ability to provide a coherent view of theater airspace is likely to reduce the number of tracking and identification issues that require resolution via voice and data communications over existing radio systems, experts say.

"We have a very robust signal. We use a lot of power, a lot of antenna gain, and a highly directional beam," Raytheon's Gecan says. "We use all the spread-spectrum technologies — spreading, direct spreading, and hopping. Everything is encrypted and we use every possible signal-processing trick in the book.

"We use low probability of intercept waveforms," Gecan continues. "So what we end up with is an extremely robust signal that can withstand immense amounts of jamming and still get the job done. By the very nature of the network, it can beat a jammer a lot of times by going around it; instead of talking directly between two nodes, we will talk through a third. We can do that very quickly when we want to. A lot of testing has been done to try to take the network down with jammers and so on and it has always withstood those. And I can't really conceive of a situation where an adversary could break into the network to spoof us."

Among the aircraft fitted with CEC will be the U.S. Navy P3 Orion maritime patrol turboprop, pictured above as it passes by Japan's Mount Fuji.

Identical algorithms filter and combine data from each unit linked into CEC to form one common air picture that is distributed back to all units, even those not actually part of CEC. Once received, each unit combines the CEC picture with data from its own radar systems, using the same algorithms. In its distributions, CEC sends radar-measurement data — not tracks — from each contributing unit to all recipients. Those communications between units are in pairs, using short transmit/receive periods over a narrow directional signal. This makes the data available in near real-time and reducing the possibility of jamming to near zero.

"CEC is a real-time sensor fusion network using the RF spectrum as the communications channel," Busch says. "As such, to participate in the network — and to receive the real-time benefits of composite tracking where each object in the airspace is represented by one track composed of sensor measurements from multiple geographically located radars — one would need to use the same security solutions. Current integration activities with other services use this same approach. In the future, as CEC data export to other near-real-time systems is implemented, alternate implementation for data security may be feasible. However, the level of requirements to protect the CEC information will remain intact."

CEC has been designed to operate in a host of combat environments. While the specific threats to the system are classified, program office officials say it has been extensively tested to validate performance under all envisioned threats.

"CEC functions as an element of the combat system. As such, it operates within the weapons fire control envelope," Busch says. "This requires a high degree of data integrity and timeliness that are not necessarily required by general military communications. The communications requirements within CEC also demand a communications channel that operates at 100 percent duty cycle in a variety of threat postures. For these reasons, the DDS was developed as a dedicated communications network. The security needs for CEC are consistent with the needs of other elements of the weapons systems."

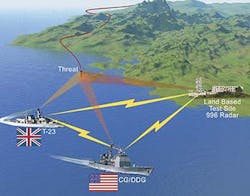

The British Royal Navy also is a CEC participant; the first system to be delivered to the United Kingdom (U.K.) in January 2002 for integration into a land-based test site with the U.K.'s Type 23 frigate, that ship's Type 996 medium-range surveillance radar and combat system, and their Successor IFF.

"Once that is complete, they'll do some testing with U.S. assets en route to the Mediterranean," Clegg says. "Their goal is to buy up to 17 systems for inclusion on Type 23 and the new Type 45 anti-air warfare platform, which is similar in mission to our Arleigh Burke DDG 51s. The Type 45 will have its own phased array radar [SAMPSON, a new multifunction radar similar to the AN/SPY-1] and PAAMS [Principal Anti-Air Missile System], their primary air defense weapon. That integration will occur in the 2007-09 timeframe. Integration of the Type 23 will begin around 2005, with deployment of all assets by 2007. For the UK, it is a stepping stone from those ship integrations to their variant of the Patriot ground-based air defense system — and their new aircraft carrier, which also is likely to have E-2C Hawkeyes on board."

The U.S. Navy also has identified — but not yet approved — other potential CEC partners, including Australia, Japan, Spain, Norway, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and Canada. Spain, Norway, and Japan all operate the Aegis combat system, with SPY radars and Aegis missiles, making CEC a "plug-and-play" enhancement for them. The global market for sensor networking systems is estimated at $4 billion through the end of this decade.

The next step for the U.S. program is for the Navy to present the TECHEVAL and OPEVAL test results — along with production, fielding, and budget plans — to a Defense Acquisition Board, currently scheduled for November. If approved by the DAB, the Navy then will secure authorization for full-rate production of about 1600 systems for fleet-wide fielding. Raytheon is currently producing more than 50 CEC systems under LRIP contracts.