Market for homeland security electronics potentially worth $billions, but slow to develop

by John Keller

Sensors and information-processing technology represent some of the hottest prospects for electronics suppliers in the emerging homeland security market.

Although this market is still in its infancy one year after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, experts say the ability to detect weapons and potential criminal intent, as well as the ability to correlate and communicate terrorist activity quickly around the world, top their wish lists for homeland security electronics

Annual U.S. federal spending for homeland security electronic components, subsystems, integrated systems, and software is broadly anticipated to be between $8 billion and $15 billion over each of the next five years, perhaps even more. If additional catastrophic terrorist attacks happen on U.S. soil, or against U.S. interests overseas, that level of spending could grow substantially larger than $15 billion, experts predict.

Government and industry experts speculate that post-Sept.-11 stepped-up security for transportation, commerce, and governmental activities will generate demand for government homeland-security spending in 2003 of $42 billion for goods, services, and staffing.

null

That number refers to spending in the future U.S. Department of Homeland Security alone. Additional homeland-security spending in the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Justice, and other federal agencies, has the potential to raise that figure to as much as $52 billion in 2003, experts say.

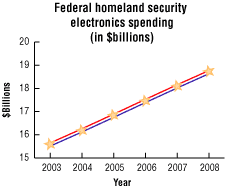

Officials from the Government Electronics & Information Technology Association (GEIA), a sector of the Electronics Industries Alliance (EIA) in Arlington, Va., are predicting 20-percent growth in U.S. homeland security spending between 2003 and 2008 if — and it is a big if — no other major terrorist attacks happen, says Dennis McCallam, co-chair of the first GEIA homeland security market study, which was to be released in late October.

McCallam also is technical director of information warfare research at the Northrop Grumman Information Technology division in McLean, Va.

null

Conservative estimates place the electronics content of homeland-security spending at between 20 and 30 percent of the total, possibly quite a bit more. McCallam points out that GEIA experts in their first homeland security-spending forecast are purposely not breaking out electronics content of this part of federal spending. Next year's five-year forecast of homeland security spending may include electronics content, he says.

Although the homeland-security spending picture may appear lucrative today, in truth, no one has a solid handle on how this market will emerge over the next several years; it is too early to tell.

Frustrating experience

Some, in fact, who endeavor to be among the first in this market claim their efforts thus far have been largely an exercise in frustration.

Homeland security electronics "is an interesting market, to say the least. Everyone says there is a ton of money out there, but no one can find much," says Steve Larsen, president of Tactical Survey Group Inc. of Crestline, Calif. "It's more posturing right now than anything else."

Tactical Survey Group specializes in software that its leaders call "immersive imagery" that enables first-responders, such as firefighters, and police, to get quick access to situational information independently of the Internet, communications satellites, or even the local power grids, Larsen says.

The Tactical Survey Group software, which uses Microsoft Internet Explorer 4.0, is designed to run on ruggedized laptop computers or wearable computers.

"The people I talk to are, by and large, very frustrated now by the whole homeland security paradigm coming from the U.S. market," Larsen says. "Everyone says there is a whole bunch of money out there, but the money seems to vaporize when it comes time for the rubber to meet the road. Very few companies have been funded to do any work."

McCallam, who is no stranger to government procurement, says he can understand the frustration. "We may be on it too early," he says. "In the normal governmental cycle, some things just don't happen the next day." Experts say a realistic expectation of when substantial federal homeland security spending will move from congressional debate to actual contract awards will be during the next 18 months to three years.

Electronics opportunities

Opportunities for homeland security, experts say, will revolve around finding new and innovative uses for existing electronics technology, rather than in developing large amounts of new equipment.

"The challenge for homeland security is integration; how do we get all this together?" points out Carmen Luvera, chief of the information grid division of the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory Information Systems Directorate in Rome, N.Y. Much of the most promising technology for homeland defense involves computers, databases, communications, and other information technology, Luvera and other experts say.

The new generation of so-called "smart cards," which contain digital information of cardholders on solid-state memory devices embedded in the cards, are prime candidates for homeland security applications, Luvera says.

"We need to add to smart cards some biometric authentication for card holders to get access to any government computer," he says. "In this way we can know when hackers are trying go get into our systems." Some of the same smart card technology also could apply to intrusion-detection systems and computer network analysis, Luvera says.

"The driving thing deals with visualizing and integrating information from disparate sources," McCallam says. "These are all databases that are not the same, which are different technologies." He says homeland security experts need the ability simultaneously and on the fly to query many different databases — some old and some new — to glean vital information in the global war on terrorism. "That's a tough problem," he says.

"Anything that integrates information is a hot technology" where homeland security is concerned, McCallam says. "We need to be able to let disparate systems talk to each other, and the ability to mine the data and draw knowledge from that data."

Among the most important homeland-security capabilities to develop, McCallam says, is what he calls "nonrepudiated authentication" — or the ability to verify that people are in fact who they say they are.

"Today that is based on a badge or license," he says. "We will be moving to portable biometrics, with smart cards that could have biometric information, where the card, the cardholder, and something else might help identify the individual." That "something else," he says, might be fingerprint, retinal scan, or some other physical trait to verify a person's identify.

McCallam says his most important advice for those seeking to buy or sell in the homeland security marketplace is to "think outside the box ... way outside the box. Look at what we are trying to protect against — something that doesn't follow the rules and is unpredictable." Otherwise, he says, security personnel will have difficulty staying one step ahead of the terrorists.

Agency partnerships

Officials of the Air Force's information grid division are trying to boost homeland security efforts by blending research for military and civil law enforcement applications, Luvera says.

The Justice Department's National Institute of Justice in Washington provides funding to Luvera's organization to help pay for developing technologies for law-enforcement and homeland security. Among the technologies chiefly under investigation in Luvera's group are concealed weapons detection, cyber crime forensics, voice recognition of different languages, and speech processing. This work complements the organization's Air Force-funded research in information security and information assurance.

"We now have a law-enforcement test bed activity inside our law-enforcement analysis facility," Luvera says. "The DOD is working with the Justice Department to transition law-enforcement technologies. Government research and development is finding its way into the open market."

Other DOD research labs, likewise, are trying to apply government-funded military technology to homeland security. That job is rarely easy.

"One of the biggest challenges we have is money. It is very expensive to transition technology, and it is a long process," explains Patricia Swanson, senior general engineer and chief of the Homeland Defense Technology Office of the Air Force Research Laboratory's directed-energy directorate at Kirtland Air Force Base, N.M.

Swanson's group is in place to move directed-energy technologies such as high-power microwaves and lasers to police, firefighters, emergency medical technicians, and other members of the so-called "first-responder" community.

"What we need most from industry is partners, or companies willing to work with us in cooperative ventures to help us get our technologies mass-produced and into the hands of the first responders," Swanson says.

The emphasis in Swanson's group is not necessarily to develop new technology, but to use existing technology for homeland security uses. "The taxpayers have already paid for these technologies," she points out. "Now we can use those technologies in another area and get twice the bang for the buck."

Swanson and her colleagues are asking members of the first-responder community for ideas on how they can apply Air Force directed-energy technology to homeland defense. "The biggest things they are requesting are sensors that can detect chemical, biological, and radiological threats," she says. "Given the anthrax situation, and the open sources we can read of what al-Qaida has, it makes sense that this is a concern."

Some of the changes necessary in the first-responder community to improve homeland defense do not involve ad-vanced technology, but rather a change in mindset, Swanson points out.

"The picture that is coming clear is that all of them — police and fire — were just not prepared for a war on their soil," Swanson says. "They are used to stopping the car for speeding or DWI, while the fire guys go to a house fire or business fire. They were not prepared for the idea that this is enemy-caused.

"They're having to rethink and retrain to respond to this," Swanson continues. "The military is always thinking of an enemy. It is a mindset that first responders go through to think more like the military thinks. Now when they go to a call with many victims, they think about whether this is an accident, or will they need to preserve evidence."