Military organizes for cyber warfare

U.S. warfighters work aggressively to protect computers and networks, just as they would do to protect territory, airspace, sea lanes, and access to space. By J.R. Wilson

The ubiquitous use of computers has elevated the significance of military signals intelligence (SIGINT), imagery intelligence, geospatial intelligence, measurement and signature intelligence, and technical intelligence to far greater significance than ever before.

That same explosion of technology also leads to the rapid evolution of two new classes of military conflict: electronic warfare (EW) and cyber warfare (CW). It is the Pentagon’s responsibility to keep America and her allies at the cutting edge of offensive and defensive EW/CW — and to use all of its ISR capabilities to know and understand what EW/CW abilities that potential adversaries employ.

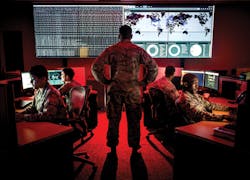

Cyber warfare specialists serving with the Maryland Air National Guard’s 175th Cyberspace Operations Group engage in weekend training at Warfield Air National Guard Base in Middle River, Md.

“One of the biggest challenges we have is just keeping up,” admits Giorgio Bertoli, senior engineer at the Intelligence & Information Warfare Directorate (IIWD) within the Army Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC) at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md.

“The Internet is only 30 years old, yet look at how much it has grown in just that time,” Bertoli says. “So there’s no reason to believe the next 20 or 30 years will not be just as changeable — from the Internet of Things, to autonomous vehicles, and to wearable computing.

“Trying to keep up with those is a major challenge,” Bertoli continues. “The Army is embracing this change and trying many ways to change their processes to improve their speed of capability enhancement, and their speed of acquisition. There is still a lot of work to be done, but we are aware of pending challenges and gearing-up to support those.”

SIGINT was born in January 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, when a British cruiser intercepted a wireless transmission to mobilize the Russian fleet and passed it on to Japan, then a British ally. It was the first act of electronic warfare, defined by the military as any action involving the use of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum or directed energy to control the spectrum, attack an enemy or impede enemy assaults by denying an opponent the advantage of, and ensure friendly unimpeded access to, the EM spectrum. EW can be applied from air, sea, land and space, and can target humans, communications, radar or other military and civilian assets.

Targeting computers

Cyber warfare represents the use or targeting of computers, online control systems, and networks through offensive and defensive acts of electronic espionage and sabotage. While it often is equated with EW, which is the subject of several programs and studies throughout U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), cyber warfare has been declared a domain of war with the 2010 creation of the joint U.S. Cyber Command, which brought together the individual cyber capabilities of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines.

China, which has touted its intention to become the world’s dominant cyber warfare superpower, also has unified its cyber capabilities. Russia has employed cyber warfare at least twice in the past decade — in its 2008 military incursion into Georgia and in a 2014 cyber attack on Ukraine.

Personnel of the 780th Military Intelligence Brigade set up deployable cyber tools overlooking the mock city of Razish at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, Calif.

Israel also is considered one of the world’s new breed of cyber super powers, based in part on its estimated 10 percent share of global computer and network security technology sales.

While not as active or public as the others, the United Kingdom in recent years has invested heavily in expanding its cyber capabilities to become the European center of cyber warfare technology.

Although less is known about the cyber warfare developments of Iran and North Korea, of those tightly closed societies are suspected in several cyber attacks — North Korea against U.S. corporations like Sony, and Iran in a host of attacks across Southwest Asia — especially against Saudi Arabia.

Some pundits have declared the world has entered into a new, multi-polar Cold War, with its own cyber warfare equivalent of the original Cold War’s doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), in which the U.S. and Soviet Union refrained from the use of nuclear weapons because the other side would respond in kind. While this new, unofficial “digital equilibrium” has been followed by the five cyber warfare superpowers, Iran and North Korea have launched serious attacks, with Iran, in particular, seeking to cause real damage.

In the event of a direct conflict between any of the Five, however, each nation’s full cyber warfare capabilities likely will be employed, possibly as a first strike. That still may be avoided, especially as artificial intelligence (AI) comes into play, making cyber warfare far more precise and effective, says Richard Wittstruck, associate director, field-based experimentation and integration at CERDEC’s Space and Terrestrial Communications Directorate (STCD).

Parallel attacks

“In field artillery, we can have single shots or volleys,” Wittstruck explains. “In cyber, it’s very rare to have a single-shot weapon; it’s usually multiple parallel attacks in hopes one or more strikes hit the target. Artificial Intelligence (AI) will enable offense to do more of those attacks, but also allow defense to put up more barriers simultaneously. So you really will have machine-to-machine warfare. AI may become the nuclear deterrent element, because you know I can do it, I know you can do it, so we go to the negotiation table — digital MAD. Still, the general public needs a better understanding of cyber warfare.

“We keep speaking in geek-speak within the community, and until we can translate that into terms the average person can understand, it will be hard to help people understand cyber is not something foreign; it’s just a new environment we operate in,” Wittstruck says. “In some ways, it’s a generational thing. Those who grew up in a digital world — born with a computer in the crib — are very comfortable talking about all these terms, but the digital dinosaur is almost still trying to learn how to spell cyber.”

This holds true for the military, as well — even though each service has a cyber component in CYBERCOM, and DOD puts increasing levels of people and money into cyber research.

The Cyber Operations Center at Fort Gordon, Ga., is home to signal and military intelligence noncommissioned officers, who watch for and respond to network attacks from adversaries as varied as nation-states, terrorists and “hacktivists.”

“A lot of the government side is a little helter-skelter on cyber,” says Steve Edwards, director of secure embedded solutions at the Curtiss-Wright Corp. Defense Solutions Division in Ashburn, Va. “We don’t do back office enterprise systems; we deal with hardware that gets deployed air-land-sea. There are lots of people involved and they’re still trying to figure out how to have a cohesive strategy.

Everyone has his own opinion about what’s important in cyber warfare, Edwards says. “Even with commands in the same service, you get different perspectives. Within each division, they are working on that. We’ve taken part in a couple of meetings on the Air Force side and the standardization push they’re trying to make across the Air Force, but it’s a slow process.”

Under today’s military structure, the individual service cyber commands focus on the needs of their warfighters. Some of the technologies and materiel are the same, but how they are applied can be different. CYBERCOM functions as an umbrella command, setting national policy and ensuring there is no duplication of effort.

“There also are areas of agreement and exchanges of people in terms of DOD working with other agencies, such as Homeland Security,” says Army CERDEC’s Wittstruck. “Cyber cuts across several different departments and there are interagency agreements and statutory authorities. Cyber is so prolific, every federal agency has a cyber component, which makes it a lot easier in a digital age to communicate and cooperate across those boundaries.”

Cyber operations specialists from the Expeditionary Cyber Support Detachment, 782nd Military Intelligence Battalion (Cyber), from Fort Gordon, Ga., provide offensive cyber operations as part of the Cyber-Electromagnetic Activities (CEMA) Support to Corps and Below (CSCB) program during the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, National Training Center Rotation.

Problems with cooperation

Such cooperation becomes more problematic when sharing cyber warfare capabilities among allies. “Each country has its own internal effort, but we’re still working on treaties and international law to develop a governance on cyberspace,” Wittstruck says, adding that military authorities still don’t have cyber warfare doctrine, training, leadership development, facilities, and policy completely nailed down.

In a digital world, where most technologies are readily available to anyone, coordinated, constant, and comprehensive countermeasures are mandatory.

“Cyber is the new IED [improvised explosive device], which began in the early ‘90s in Bosnia with explosives put in a pothole and covered with garbage,” says CERDEC’s Wittstruck. “It was prolific, effective, and random and anybody could do it who had the knowledge and access to materials. The same is true today with cyber, although they also need to be able to access a network.”

Despite this, the military can search cyberspace constantly for abnormalities or alerts that something has changed. “The challenge is things can change very rapidly, so in a matter of milliseconds, you can go from having a good day to having a bad day,” Wittstruck says.

“Once something does occur, it doesn’t mean that’s a combat loss; you just have to manage it, determine the effect on your fighting capability, and have a contingency plan on getting back.” This is called a primary alternate contingency emergency (PACE) plan. “This is a combined arms fight,” Wittstruck says. “Cyberspace is what some call the fifth domain and we bring many of those combined arms principals to bear on force effectiveness and planning.”

Defensive cyber warfare can face a variety of attack types, depending on whether the enemy wants to deny, degrade, or disrupt computers and networking — or any combination of the three. It also depends on the target — military enterprise, subnet, platform, individual warfighter or unit. Or they may target civilian infrastructure and just turn the lights on and off to tell civilians they are no longer in control and can be attacked at any time,” Wittstruck says.

Difficult to trace

Modern military satellite surveillance covers most of the planet, making it virtually impossible to hide an attack by missiles, aircraft, ships or land forces, enabling the target to strike back against the attacker’s home base. That is not the case with a cyber attack, however, which is extremely difficult to backtrack. Even if a cyber attacker can be traced, it can be impossible to tell if the attack came was the nation from which the attack was launched, a non-state group, or even individual operating from within that nation.

Sorting out cyber attackers is called cyber forensics, which has had exponential growth in recent years as the cyber threat has become more pronounced. Backtracking requires that the attack is still in progress. Once it ends, different methods must be employed. Still, without that critical link between the attacker and the target, determining the attacker’s IP address is almost impossible with current technology.

More frustrating to cyber defenders is how cheaply perpetrators can launch cyber attacks; it doesn’t require a lot of money or infrastructure, only the necessary skills and the ability to access the target.

How a cyber attacker gets to the target represents another line of investigation. Does the attacker have someone on the inside helping, or is it a high-level hacker who can penetrate network defenses without a care if the target knows about it or not. If the same person makes multiple attacks, he or she is likely to leave digital fingerprints reflecting the techniques they use, which may help identify and locate the attacker. For now, however, cyber forensics is unlikely to find a “smoking gun”.

The effects of a cyber attack can last long after the attacker has disconnected. Shutting down a power grid, for example, could leave thousands, even millions, of people without electricity to heat or cool their homes, pump gas for cars and trucks, light homes and streets (an open invitation to looters, who also would not have to worry about alarms), get fresh water because the pumping stations are down, treat patients in hospitals The only remedy is for the power company to have the necessary remediation, redundancy, and repair capabilities in place; how quickly it performs those functions will make the difference between degradation, disruption and denial.

Even so, not everyone sees cyber as a potential 21st Century Pearl Harbor, as several government officials have warned.

Keeping the lid on

“Granted, there are thousands of attacks every day on various targets, a lot of them using automated systems churning away and looking for weaknesses or openings,” says CERDEC’s Bertoli. “For the most part, commercial service and security providers have made great strides and most of those activities are blocked at various places within the infrastructure.”

For would-be cyber criminals, however, pulling off an attack is easier said than done. “Cyber attacks are not nearly as easy to pull off as you might assume,” Bertoli says. “Going after a hard target requires some serious effort — you have to know what defenses the target has, for example. So while there are threats we must take into consideration, it is unrealistic to believe one guy in his basement, acting alone, could bring down the Internet or any major infrastructure system.”

Perhaps the notion of a Cyber Pearl Harbor is somewhat overblown. “Could an adversary mount a meaningful attack against a critical infrastructure component to cause harm? Absolutely,” he says. “But could it cause the same kind of loss of life as a Pearl Harbor or 9/11? Probably not. Our power structure is pretty resilient and could recover from an attack fairly quickly. I would not put cyber in the same category as a Pearl Harbor or 9/11. I don’t think anybody would really want to make that kind of cyber attack on its own, except perhaps a terrorist organization. So while some scenarios are pretty scary, I don’t think they jump to that level.”

To help prepare for and defend against cyber attacks, the U.S. military services have begun including cyber in military exercises, including some, such as the Army’s Cyber Blitz, dedicated to cyber warfare. The Army has conducted three such exercises, each incorporating what was learned from previous efforts and the latest technologies.

Cyber Blitz 3 involved more than 700 participants from 25 organizations, including the Marines. The integrated campaign has matured through those exercises to improve how to go “from space to mud” in support of the tactical commander in a fight against a regional peer in kinetic and non-kinetic effects, such as cyber.

“Cyber Blitz was born as the result of the Cyber Center of Excellence and CERDEC, back in 2015, wanting to demonstrate and validate the concepts of that doctrine before it was updated to the Army writ large,” says CERDEC’s Wittstruck. “We established our first Cyber Blitz in 2016, in which a unit had to fight their way through a validated scenario, not just kinetic effects in which they were well versed, but also cyber attacks, GPS denial, spoofing They had to learn, sometimes on the fly, how to deal with that. The Army’s cyber warriors don’t operate in a vacuum, but in a combined arms fight. So we focused on a brigade fight working with partners.”

Keeping in practice

Cyber Blitz 2019 will pivot to the Pacific and work with Pacific Command to determine what elements should be the subject of focus. Wittstruck predicts they will integrate cyber into some as yet unnamed element in that exercise.

Cyber defense is not exclusively an end user concern, it begins at the beginning, with the contractors who build the systems, subsystems and components that comprise a cyber or cyber-protected program.

“The threats are ubiquitous,” notes David Sheets, senior principal security architect at Curtiss-Wright Defense Solutions. Defense contractors, he says, “have to understand the risks and make sure we have all the correct procedures and processes in place so we can tell our customers we have done the due diligence to assure they will have a secure system once they put all the boards and such together. That impacts our supply chain management, production flow, all of which have to go together to insure there are no kinks in the armor as you integrate these systems.

“Multiple people have been trying to wrap their heads around the intersection of cyber security and safety critical systems and how those work together,” Sheets says. “I don’t think anyone has a good answer to that yet — there is a lot of synergy in some areas, while in others, cyber may say one thing and safety something else.”